The first thing Terse says when I arrive to learn jaki-ed weaving from her is that this type of weaving almost disappeared. She says I need to write about how she revived it. How she pulled the strands of leaves and the patterns that look like stars unblinking from worn out photographs in the only museum on island. Despite the absence of a teacher, despite elders buried with the instructions still grasped between fingers, she pulled strands from an emptiness, from a void and a hunger within herself and she created.

Terse wasn’t allowed the privilege of schooling. She was asked to stay home, tend to the children, clean the house.

The poet June Jordan says the creative spirit is nothing less than love made manifest.

I imagine Terse roaming our small, dusty museum. “I didn’t have those fancy phones you use,” she tells us. “I had to stare at the patterns to memorize them. And then I’d go home and try to replicate what I saw. It wouldn’t be right – I’d have to unravel and start all over again until I got it right.”

This was how jaki-ed was revived. Despite being set aside, deemed unworthy and unnecessary once clothes came on ships to the shore. Jaki-ed, the style of fine weaving we once used to make nieded, our traditional clothing, was swept away. Not officially deemed uncivilized – but I suppose it sank below the waves, quietly. It didn’t cover enough of our bodies. And it was too much work. (I can attest to how much work it really is.) Instead we wove what could be sold to the soldiers and later the tourists – they wanted cigarette cases. Wall hangings. Pretty flowers for their corn-fed girlfriends waiting for them in America. One style traded for another but really it was just a different pattern for survival. One which so many women used, and continue to use to pay for school supplies and food for their children.

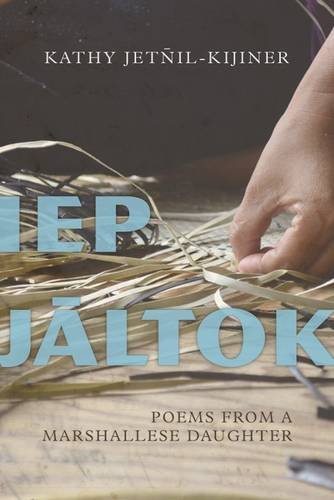

Today I am bent, back aching over my first mat, fingers awkward and uncoordinated, trying to ignore the sweat that lines the back of my legs, my neck, the oppressive heat and the ocean rising right in front of me.

And the radio drowns out the announcements of hurricanes and catastrophes, and Trump pulling from the Paris Treaty. I think about how I have yet to respond to this insane, selfish act – something we’d been expecting since he became president. I still have not found the words to capture my rage – my rage at the exit, at the inhumane act of turning away, of pretending so many don’t exist, of pretending responsibility lies with others, and not their own country.

And I am all the way out here, sheltered by rain and a weather report that there will be no flooding today. There is no flooding today. No catastrophe here. We are not scrambling to respond to a storm nearby, or to find shelter, or applying for a loan to rebuild a home, or asking our bosses for time off to clean up the water that has flooded our kitchen floors. Sometimes, it feels as if I am holding my breath. I feel as if I am gasping for air, like I am grasping for the right words.

“There’s a gap over there,” Terse tells me. She pulls my unfinished mat, all strands and holes onto her legs so she can fix it. “Like this,” she says, “like this.” I squint. I try to understand, the translation uneven, like the pattern I spent two hours trying to unravel.

“You’re going back to your roots,” says a friend later, assuming an arrival. Assuming ownership. As in these are “your” roots. When they never felt like yours to begin with. When they still don’t.

In college I read academic essays about the cultural significance of birth cords and the next day I emailed my mother without a subject heading. “WHAT DID YOU DO WITH MY BIRTH CORD” filled the body of the message and literally nothing else. She emailed back pleasantly, “I’m not sure. I think your grandmother took it to Aelonlaplap and buried it beneath a pandanus tree.”

Aelonlaplap is the island where Terse is from. The island where she taught herself to weave, where she learned to fish, climb coconut trees for herself. “Why would I need a man if I can do these things myself?” she says, laughing.

It is also the island where she saw the bombs explode. And I am reminded that our islands were literally incinerated with no other intent then to preserve their own survival. Because they don’t want us to survive – our traditions weren’t meant to survive, our bodies weren’t meant to survive, our stories were/are not meant to survive. It must be easier, in their minds, if we washed away with the rising seas.

And yet here we are. Weaving old and new. Creating as survival mechanism.

We bury girls’ birth cords beneath pandanus trees so that they can grow up to become good weavers. Boys’ birth cords tend to be thrown into the sea, to become good fishermen. I wonder, looking at my dilapidated mat, if they buried mine with the pages of a book. Perhaps they needed to specify what type of weaving I was to master. Somehow, I found the strands I needed.

I am the first to admit that despite this knowledge, despite learning and living here – that none of this has ever felt like it was mine to claim. This island is not mine. It never was. I don’t speak the language of these weavers, I speak the language with an embarrassing accent, a halting speech – yet here I am still grasping for the right sounds.

Terse tells me that she had me start out with bigger leaves, rather than the thin strands usually reserved for jaki-ed, because she didn’t think I could do it. “Your grandmother was a good weaver – her hats were really beautiful,” she tells me, smiling. My grandmother died when I was in the sixth grade, of tongue cancer. Like Terse, I struggled with communicating with her as well. Though it was worse then – English weighed down my tongue even heavier. “But you,” she says, laughing, “you grew up out there. I didn’t think you could do it.”

As she says this, I prick myself with a needle – it stings a little. It stings to be reminded that diaspora may never be enough. That I am an unfit pattern in the US, where I was raised, and as much of an unfit pattern here in what’s meant to be home.

Truth is, I didn’t think I could do it either. Move back. Fight for a homeland that does/doesn’t feel mine. Learn the language (again).

And yet.

In between the strands of leaves I can see a pattern for survival. A lesson in resilience. It’s beneath Terse’s coarse fingers, slow and steady. Even if it doesn’t feel like yours – even when you see it sinking beneath the surface, there is still a museum of memories, a corridor you can walk through, photographs you can squint at and memorize – before going home to try to replicate. It’ll be wrong, at first. There will be gaps. But you try, and try again, and then.

There it is.

Lovely that you have sabed this weaving. May we see pictures of your art.

Love Judith

Love your writing Kathy! And so happy to see more and hear more about the weaving process.