I’m back to rainy Portland, Oregon, after I spent three weeks of September in Majuro for a weaving training.

For three weeks I learned from master weavers back home – mostly under Terse Timothy, a woman elder from the island of Ailinlaplap. Terse has been credited with reviving the traditional jaki-ed weaving. It was an honor to learn from her.

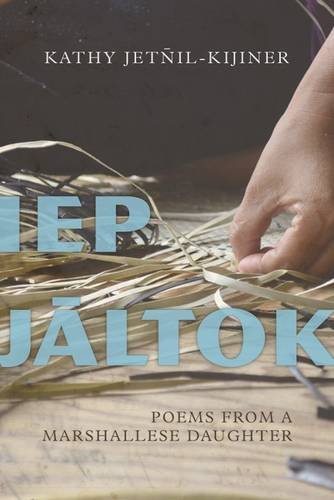

To be real though, I had never woven before this. I had zero experience. The weaving we were doing, the jaki ed, is one of the hardest types of weaving – it is a practice that weaves extremely fine leaves of pandanus into intricate mats. I initially proposed this workshop after I was approached by organizers from the Queensland Art Gallery & Gallery of Modern Art to create a new performance for the Asian Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art that would take place in Australia in November 2018. When told that it was basically whatever I wanted, I proposed weaving because I’ve long been a fan of our jaki-ed, and I even considered studying it as research at one point. Three weeks is also a lot shorter than the usual training workshop given to women in the outerislands and in Majuro – it’s usually three months.

I expected to be bad at it. The aim wasn’t to come out a master weaver. I told the weavers in our introductions as a joke that I was at “kindergarten” level and that I appreciated their patience with me. The rest of the training they referred to me as “Kinder” as in “kwon lale jaki ne an kinder e, mottan jidik emoj well look at the kinder’s mat it’s almost done.”

We wove in a hut that had just been built at the new campus for USP. The ocean faced us, tranquil and calm. Sometimes it rained. Always, we wove. If not ate, talked story, and occasionally napped. The weaving hurts your back – you are sitting cross legged, or one leg out, hunched over your mat to make sure each strand is pulled tightly from 9 – 5, every day, sometimes longer. “No gaps,” Terse always reminded me. “You have to pull up, then put it down and pull again.” The translation is suboptimal. Everything is translated in your head from Marshallese to English. But it’s never really enough.

And that’s what made the weaving difficult. I was grasping at a new art form – I told myself this. A friend said, “You’re going back to your roots” and I scoffed at the simplicity of this statement. It was trying, and failing, and trying again, and connecting, only slightly. There was never an arrival. There was a grasping. “There’s a gap over there.” There’s a gap between the words I weave inside my own head – at some point I wasn’t diligent and didn’t pull at the right words. I missed a strand.

In between Terse’s lessons “Always be aware of everything around you like our warriors. Don’t just look in front of you look to the side of you,” the radio drones on, BBC and translations of news – Texas flooded. A storm to Puerto Rico. Trump’s polarizing comments. Ongoing disputes and a sea that is rising right in front of us. I had just returned from a 350 Pacific Climate Warriors retreat, where I strategized with other like-minded islander youth representatives on a new #Haveyoursei campaign in the lead up to COP23. I think about logistics, workshops to give, powerpoint slideshows to design, the poem that lies dormant beneath my fingers.

In the weaving hut it is usually quiet. It rains and you can feel the rain all around you, a cooling mist in this heat. And Terse is tired, her back sore, so she takes off her glasses and leans over, cradling a roll of pandanus strips beneath her head.

I haven’t found the poem yet. I’m still grasping at strands, trying to find it in the lift and the pull. The weaving is not yet done. Soon. Soon.

**photos by photographer Chewy Lin

Be kind to yourself and give your heart a break if you have to. You’ve done more than you know

Thank you for sharing.

How did you find a pattern to weave?