What a weird and awful time in the world right now. When I moved back home to the Marshalls this past December, after three years of being based in Portland, Oregon, I never thought our country would suddenly be locked down, for months at a time, cut off from the rest of the world. I never thought I’d be grounded for this long. Covid seems to have grounded us all in a collective, worldwide grief.

When I first watched it all unfold, I was at a loss as to how to respond. I was used to working and feeling useful in the climate crisis – but this wasn’t the crisis I was prepared for. Since then, I’ve had some time to reflect, as we all have, on the different intersections between climate and covid, from my position here in the Marshalls.

Marshall Islands and resiliency

While the rest of the world ground to a halt, sheltered in place and quarantines, life continued to move forward here in the Marshalls. With no confirmed cases of the illness, face to face meetings, family gatherings continued.

This is where my fellow Climate Envoy Tina Stege’s words ring true to me when she said “our resilience is much richer.” We were able to manage covid because of our relative distance from the rest of the world, but also because we recognized our vulnerabilities early on. We were still recovering from a dengue outbreak months ago, an issue that has proven links to climate change.

Because of the dengue outbreak, our hospital staff and administration were overwhelmed for months. They were already painfully aware of our country’s vulnerabilities and limitations – they knew we wouldn’t be able to take the hits from covid. There is a huge potential for it to easily wipe out so much of our population for many reasons – lack of infrastructure, multi-generational households, prevalence of multiple illnesses such as diabetes etc.

There was no hubris or ego involved – we lacked the capacity, recognized it, and decided protecting our citizens’ lives was more important than the economic losses. So simple, and yet when held in comparison to countries that are prioritizing corporations over their communities and nurses and doctors, this can be considered powerful.

This is not unlike our continued response to climate change – we recognize how vulnerable we are, and we have been doing everything we can at the international, national, and grassroots level to respond to the crisis.

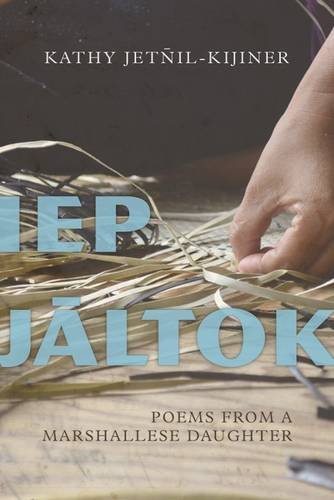

This is not to say that things are by any means perfect. We’ve sidestepped the insurmountable losses that are adding up by the thousands in western countries around the world – but we’re still feeling the economic strain. While RMI doesn’t rely on the tourism industry in quite the same way as other Pacific countries, it’s still affecting our hotel, restaurant industries and even our handicraft weavers who are no longer able to sell their goods without the tourists picking them up.

And because of the shipping regulations and the cost of flights, a lot of our businesses relying on shipments are suffering as well. I’m looking forward to hearing about an economic relief package from our National Disaster Committee for those who are losing their jobs and their means of income. We can’t pretend that just because we’ve saved ourselves so far from covid, doesn’t mean there aren’t families getting hit hard by the economic downturn.

The diaspora situation

I’d be remiss if I didn’t touch on the ways covid has been hitting our communities out in the US. The same issues that make us vulnerable here in the islands, makes us vulnerable in the US as well. But in particular, coming from low income families living in packed houses in the US makes it harder to self-isolate, or bounce back from economic losses, or turn down job opportunities that expose us to risk. When covid illnesses rose in the Big Island, it was coming from McDonald’s employees, who were then infecting family members who worked in macademia nut fields, etc. And the additional factor making things worse for our community, as well as Pacific Islanders in general in the US, is an unequal access to health care.

Melisa Laelan, the President and founder of the Arkansas Coalition of Marshallese, was quoted as saying, “The challenges that Pacific Islander communities are facing with Covid-19 are the same challenges we have been dealing with for decade.” Covid exposes not just illnesses, but also the cracks in the system that our community advocates for years have been trying to call attention to.

Despite all this, I’m really proud of the ways in which our community out there have been responding to the crisis by banding together to deliver supplies to one another, providing services to apply for unemployment (a difficult process for so many of us to navigate) and even taking a strong stance against racist remarks made by the Department of Health scapegoating Marshallese and Micronesians. We can’t control this global pandemic, but we can definitely control our responses.

Picking up the pieces

And while covid has shut down most of the world, it definitely has not shut down the effects of climate change, and here we see another intersection. In the Pacific, Cyclone Harold swept across Solomon Islands, Vanuatu, Fiji, and Tonga, leaving destruction in its wake, and urgent cyclone relief supplies were delayed due to covid. Vanuatu opposition leader, Ralph Regenvanu was quoted saying “When the Covid-19 pandemic reached the Pacific, countries were able to put in measures to limit its effects…but when Cyclone Harold hit… there was nothing anyone could do but pick up the pieces.”

Climate change effects will continue to impact the Pacific, so while the rest of the world is pivoting from climate to covid responses, the Pacific needs to maintain solidarity and pressure on countries around the world to remain committed to climate goals, and incorporating greener pathways into their recovery packages.

Celebrating the cleaner air

Across social media, tweets and memes celebrating the cleaner air, cleaner streams began to rise, just as posts from immuno-compromised friends raised awareness on the vulnerability, as well as the unique strength, of the disabled and sick communities, while statistics showed that black and brown communities were dying from covid at disproportionately higher raters.

I tweeted out later that the cost of our now cleaner environment – the millions of deaths around the world – is way too high, and I for one don’t agree with celebrating it. It smacks of eco-facism. I’m glad our land, air, and sea got a chance to breathe. This is what indigenous, Pacific folks and environmentalists have been campaigning for for decades – ways to support our environment, but without the heavy cost of lives.

Those of us knee deep in the work know that there are efforts being made at the technical level to make sure that we recognize how climate change disproportionately affects women, people of color, the sick and disabled, queer communities, youth. Meaningful climate work recognizes the vulnerabilities in the system, and seeks to address them. Meaningful climate action doesn’t leave anyone behind.