** This was a keynote I wrote for 2020 Pacific Climate Change Conference in October where I was asked to reflect on the past COP25, the upcoming anniversary of the Paris Agreement, and youth and arts (kind of the usual actually).

Iakwe aolep im kommol to the organizing committee for this opportunity to speak to you all today and share my reflections on COP25. As a relatively young person in this space, I’m humbled to be able to share my observations with such seasoned professionals who’ve all been negotiating and strategizing to protect our islands for years. I recognize these efforts, and the path laid before me, paved by leaders such as the late Tony deBrum, my granduncle and former Minister of Foreign Affairs and Senator for our islands who helped “grandfather” the Paris Treaty. We reach the 5th anniversary of the Paris Treaty this December and this will be an important time to reflect on how far we’ve come, and in particular how far the Pacific has pushed and led the rest of the world in climate justice. Lord knows we’ve carried the rest of these industrialized, colonizing nations on our backs.

I didn’t enter the climate realm in a very conventional manner. It started, as it did with many of us, with a deep love for our islands. A deep love that translated into an urgent fear when I experienced my first king tide flooding. This was when I wrote my first spoken word piece on climate change. After my performance at the UN I was thrust further into climate conferences – but always as an opening or closing speaker. I was the cherry on top – not the substance. Just a sweet ending. I was told to perform my poem and then sit down while the professionals spoke. Arts still has a long way to go in being recognized as a viable channel in climate communications and spaces.

Besides the arts, I’ve been coordinating climate actions alongside my cousins and friends since I returned home from college through our nonprofit Jo-Jikum. Around the same time I wrote my first poem on climate change, I was also meeting with other young people, sharing our fears over pizza and beer, coordinating marches and photo demonstrations with 350 Pacific Climate Warriors, draping cloth over a tin fence for movie nights for neighborhood kids. Since then, our organization has grown to include programs like our Climate Arts Camp, the second one implemented just this past summer, where we teach high school students how to use the arts to raise awareness on climate impacts, transforming them from passive victims to creators and artists.

I wanted to learn more. I wanted to wade further into the trenches. So I’m really grateful that our government gave me an opportunity to be Climate Envoy, where I got to see and experience COP25 as a poet activist and also experience the negotiations and the political backroom meetings between representatives.

So these are some initial, and I’m sure what folks will see as naive reflections on COP.

COP is an abusive space for Pacific Islanders.

It’s an abusive space for people of color, the global south, any disenfranchised so-called ‘minority group.’ It is a battlefield that requires strategy, an inordinate amount of funding in the case of first world countries, and for our countries in particular, grit. I honestly don’t love how often militaristic language gets co-opted to discuss the climate movement, and yet the cruelty of the COP negotiations space brings these similarities to mind. Emotions get shelved, and though you may be fighting for the survival of your country, you must deliver your interventions calmly or you lose the floor.

A friend of mine, a fellow academic and activist once asked me if the UNFCCC process was worth it. I said yes, because I recognize that despite the problematic nature of the process, it’s the only one we’ve got to deal with this global issue. 0.00001%. That’s the percentage of global emissions RMI contributes to the world. I’m sure that percentage varies only slightly through the rest of the countries of Oceania. We all carry so much weight on our backs.

Tony was known for his charisma. For his ability to make everyone in the room feel seen. I don’t have that kind of charisma. But I have the churning fury that rippled beneath his surface. And as an artist, I’ve found ways to channel the jumble of emotions I struggle through into creative work.

Inundation

The poem I wanted to share with you all today was written shortly after COP25 for an exhibition called Inundation with UH Manoa. I collaborated with my friend, Kanaka Maoli artist Joy Enomoto on our installation. I’ll read you the description:

“Stepping through a doorway of hanging Marshallese baskets, viewers enter into a watery space evoking competing gestures of sonic vibration. A single hanging “sounding line,” historically used for measuring shallow bays or “sounds” for better navigation to port, references the development of hydrography, and with it the colonization, militarization and industrialization of the Pacific. This antiquated tool of ocean exploration and mapping was replaced by sonar (which literally uses sound waves to measure the ocean floor) by the early 20th century. Sonar was used in the atomic testing of the Marshall Islands to measure the extent of the damage to land and reef systems. It is now used for deep-sea oil exploration, obliquely referencing climate change and sea level rise.

To counter these histories of underwater “soundings,” the artists remind viewers of other important oceanic voices. On the far wall is a drawing of a humpback whale composed with National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration reports. The humpback whale is an important ʻaumakua in Hawai‘i, embodying human responsibility to hoʻomana and hānai, to worship and to feed, ancestors present in all the elemental realms. The entire space resonates with Kathy Jetn̄il-Kijiner’s voice reciting a poem composed specially for Inundation. Together, Jetn̄il-Kijiner and Enomoto offer a decolonized hydrography of the Pacific.”

To be honest i struggled with what to write for this installation. When my friend said she wanted whales to be incorporated into the installation, I struggled. Whales are cool, but I haven’t developed or explored a relationship with them the way many of my poet friends or my “weird friends” as my old-school traditional Marshallese parents would say. How was I going to connect whales, militarization, and COP??

I settled on something my friend Matthew told me in Madrid. He told me that the three words that watered down the commitments in the Paris treaty the most were “Decides” “Urges” and “Requests.” I scribbled these words down at the top of my journal, and turned back to them when I started my reflections. And this is the poem that came out.

The poem

How to use the forks and the knives

When I think back on COP25, I am also reminded of something my friend Brianna Fruen said on a panel with me. Brianna is a brilliant Samoan youth activist I look up to and admire. She said that as a youth activist she always wanted a seat at the table, but that once she got that seat she realized she didn’t know how to use the forks and the knives.

I haven’t told Brianna, but this quote has been guiding so much of my work throughout this year. RMI recognizes the importance of youth in the climate movement. This was why we introduced the Kwon Gesh pledge at the Climate Summit last September, alongside Ireland, a pledge developed by RMI youth activist Selina Leem, another brilliant woman in her own right. Countries that sign the pledge commit to meaningfully incorporating youth into climate decision-making processes. But this is a lot easier said than done.

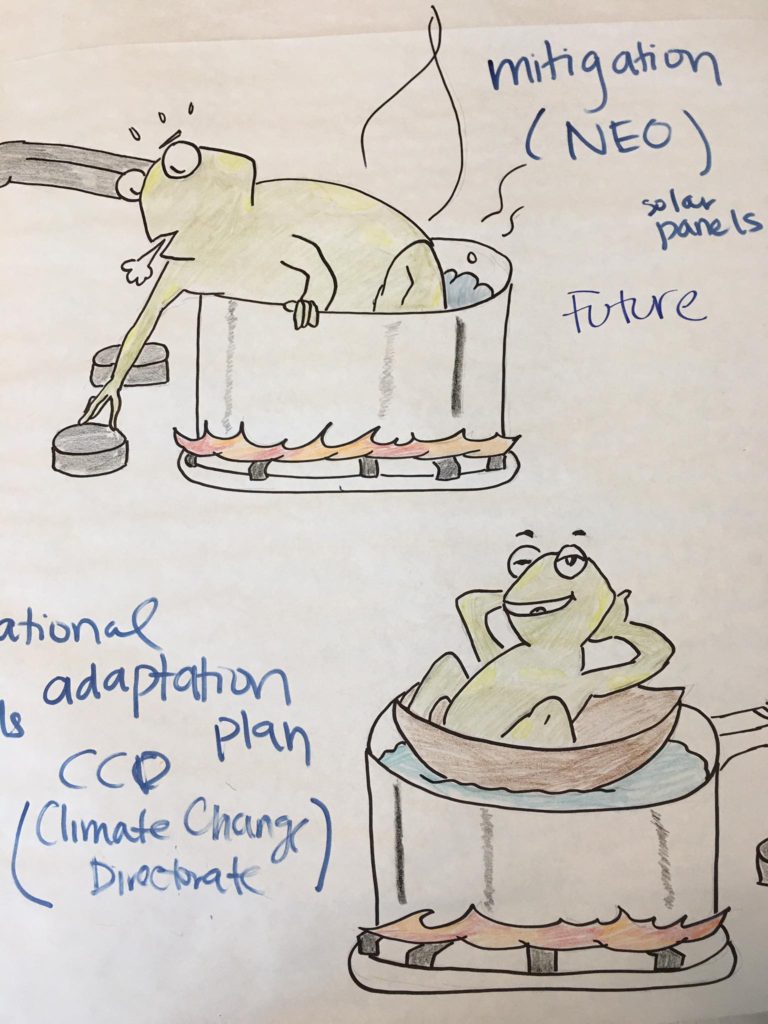

Through my two positions as Climate Envoy and Director of Jo-Jikum, this is something I’ve been exploring and seeking to understand. How do we make sure our youth have a seat at the table, but also know how to use the forks and knives? For myself, I want to make sure we provide meaningful trainings that teach the complicated language of this climate realm. It means making sure we provide the space, the tools, and then also the holistic support to them as individuals. I did a pilot training just this past Monday for the interns from our Climate Change Directorate Office, Jo-Jikum, and the National Energy Office. It started with a very basic discussion that admittedly many of our own government employees outside of the climate department struggle to understand themselves: the terms mitigation and adaptation. I used a really simple cartoon I found online – I can no longer find the link to it unfortunately but if anyone knows who drew this originally let me know.

Either way, adaptation means we can no longer wait or urge the world to lower their emissions. We need to protect ourselves. Adaptation. This is where I feel the most lost in the weeds, the technical work of developing our national adaptation plan, or our survival plan as we’ve called it. This is a plan that centers human rights, and will engage a thorough community consultation throughout our islands that will collect observations of change as well as raise awareness on what’s to come. It will seek to answer some of our toughest questions – how do we measure cultural loss? Which islands are most at risk? When will we need to migrate? What would happen to traditional land tenure rights if islands are lost?

I’ve been struggling lately with the weeds. I can’t see the forest. Poetry and art demands that we see the forest. This is why I advocate for the arts. We need to see the forest, to have vision and push for a change in collective consciousness. Yes we are attending meetings, developing frameworks and terms of references, implementing workshops, and collecting meeting minutes, doing the damn work. No one can accuse the Pacific of idly standing by, and if they are they just haven’t done their research.

But there’s a reason why we’re doing this work. There’s a forest, or should I say, an ocean, of reasons. And I encourage us to take the time out as often as needed to reconnect to those reasons. This is a long game, not a short one. And we need our youth to shore up their reserves, and the elders longest in the game to pass down their knowledge. It’s harder and slower, this process, but it’s worth it. We’ll get farther.