Runit Dome: the focus of my new poem. PC: Greg Nelson

For my first blog post of 2018, I thought I’d take some time to reflect on my first poem project of the year – the Dome Poem, as I like to call it, which focuses on the Runit Dome.

The Runit Dome was once just Runit – one of the islets that make up Enewetak atoll. It was incinerated thanks to nine nuclear tests being detonated by the US. In its place was a crater that was dubbed the “Cactus Crater.” Despite protests from the EPA and the people of Enewetak, over 4,000 U.S. servicemen gathered large amounts of highly radioactive plutonium-239 (with a half-life of 24,000 years) ground it into a concrete slurry, and pumped it into the bottom of the Cactus crater, along with 437 plastic bags of plutonium fragments that crews had picked off the ground and over 104,000 cubic yards of contaminated soil. This all took place during the cleanup of Enewetak from 1977-1979.[1] The people of Enewetak, who were forcibly moved to Ujelang during the testing, returned 50 years later, and continue to live there to this day.

I first learned of the Runit Dome when I was researching nuclear testing as a part of my high school project. There were so many awful facets to the nuclear legacy to learn at the time, that I’m ashamed to admit that this initially didn’t register in my mind. It only came home to me when I began to teach nuclear issues at the College of the Marshall Islands. What surprised me was how unaware I was of it, and how this was reflected in my students as well. It was then that I began to envision a poem video that I could film and perform from the dome itself as a way of raising awareness of its existence. As a way of making it real to myself. But also as a sort of ritual. Poetry for me is healing – what would happen if I used this monstrosity to create art? What kinds of stories would arise? What kinds of conversations would exist?

Making the “Dome Poem” happen

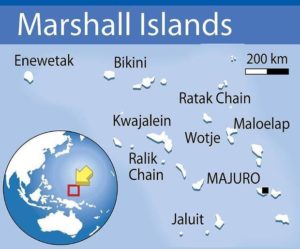

But as with anything, funding and support is needed. Especially since Enewetak is the farthest atoll in the chain and requires chartering a plane. It’s so far from the rest of the islands in the Marshalls that it has its own time zone.

Luckily my colleague Dan Lin from PREL had a conversation with friends from University of Edinburgh, and the Okeanos Foundation – and a partnership developed. The plan – so far – is to set sail on the Okeanos canoe from Majuro atoll to Enewetak atoll in February, and film a performance of the poem from Runit Dome itself (if everything works out – fingers crossed.) Besides filming the poem, I’m looking forward to meeting and talking with people from that island, as I myself am not ri-Enewetak. We are also hoping to do workshops with the community there on the UN Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons, a treaty that was recently adopted this past year to ban nuclear weapons.

In the background of writing and researching Runit, a lot of things happened around the world. Hawaii had a missile scare that lasted half an hour – with thousands of people in a panic considering who they needed to spend their last few minutes of their life with all thanks to “human error” – someone pushed the wrong button. Meanwhile Trump’s administration banned temporary visas from Haiti, Belize and Samoa. Nuclear tensions continue to brew between North Korea and the US. And my own country still has yet to ratify the UN Treaty I mentioned above.

I first learned of the treaty from the organization International Campaign Against Nuclear Weapons (ICAN) last spring. I was originally invited to give a speech at one of their events leading up to the official signing of the treaty in New York. I was already booked at the time so I offered to write a poem instead. The poem I ended up writing was “Monster” which connected Marshallese women’s birth defects from the nuclear testing with a Marshallese legend of women demons, and my own postpartum depression. It was a difficult poem to write, but it was the poem that I’m most proud of from 2017.

The journey of writing the poem “Monster”

As I move into 2018 and into my 30’s, I’ve begun to think more about where I want my career to go and what place my art and writing has in the world. “Monster” was a poem that defined 2017 for me – it was one of the few poems I’ve been happy with because of the journey it took to write it. It resonates with me especially now that I’m working on this new project – yet another poem that links to the nuclear legacy.

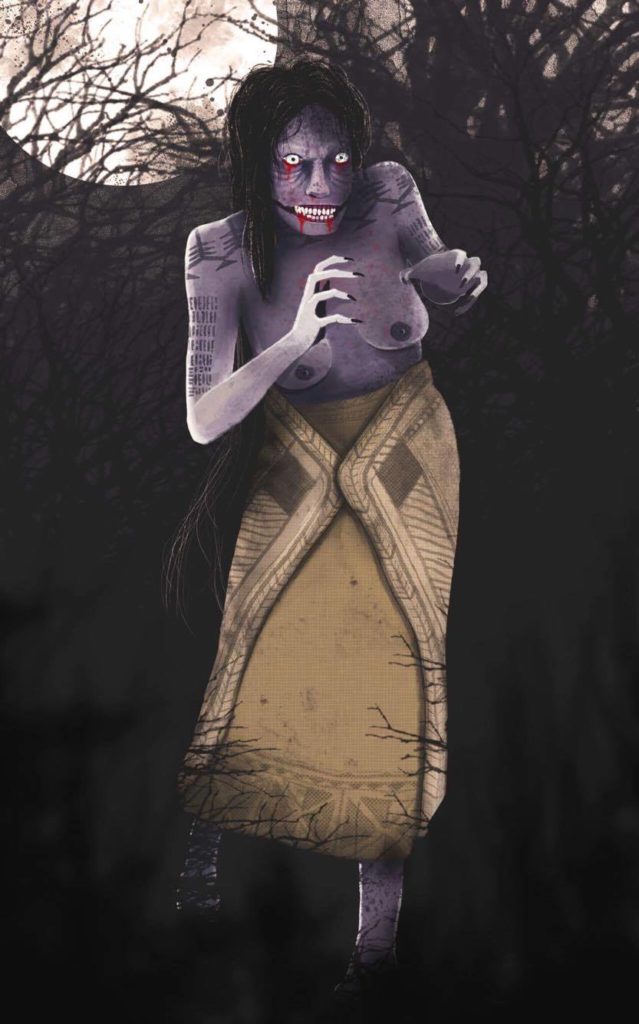

Before writing “Monster”, I spent months researching and thinking about the topic. I combed through reports and documents from Glenn Alcalay’s incredibly detailed research. I read through legends I found in Jack Tobin’s collection Stories from the Marshall Islands of the mejenkwaad, the Marshallese women demon known to eat babies and pregnant women. I asked my friend Ronnie Reimers, a Marshallese graphic arts designer, to draw what he imagined the demon would look like, so I could have a visual aid. I asked friends and family members to tell me what they know of the mejenkwaad. Most were startled and disturbed that I was asking about it at all. The mejenkwaad is known as one of our most ominous characters in our legends and stories. But I was drawn to it for reasons I couldn’t articulate at the time.

The “Mejenkwaad” – a Marshallese woman demon known to eat pregnant women and children. Depiction by Marshallese graphic artist Ronnie Reimers

Exploring my fascination with the mejenkwaad ultimately led me down the path of exploring the dark spaces of my own issues with motherhood. It was while I was editing the piece with my mentor, Lyz Soto, that I realized this. She asked me why, in the initial drafts of the poem, did I seem to be trying to rehabilitate the mejenkwaad – what was the purpose of this?

I realized that in trying to rehabilitate the mejenkwaad, in trying to envision this character as not just a demon, but as a tortured individual, to humanize her in a sense, I was actually trying to rehabilitate myself.

The mejenkwaad, birth defects, and postpartum depression

I suffered from postpartum for the first two years of Peinam’s life – I can admit that now, but for those two years I had no idea what was going on. While I saw how other women effortlessly connected to their child and embraced motherhood, I struggled to connect and to understand the anger and resentment that brewed in my chest. It wasn’t always there. But during nights when she wouldn’t stop crying, I had panic attacks that made me feel like a monster. It was something I buried and was not open about with many people – only my closest friends. I was deeply ashamed of these feelings and experiences.

During my research of the mejenkwaad, some of my own family members theorized that the mejenkwaad legend might have been created to discuss postpartum depression – that it was a way in which our ancestors tried to understand the deep sadness that can translate into a sort of madness after the initial trauma of birth. Tobin noted this as well: “The mejenkwaad concept may be based upon anxieties of women (and their relatives) during pregnancy. The mortality rate of both mothers and babies may have been quite high.”[2] There are some cultural beliefs that women shouldn’t walk alone at night or be alone at while pregnant – that in doing so, you risk turning into a mejenkwaad.

I wondered if this must have been how the mothers who gave birth to jelly babies first felt. I wondered if they considered themselves monsters. I read quotes from Alcalay’s research from women who admitted that they hid these births initially – thinking it was punishment for something they did, or some sort of retribution. It was a quote from Lijon Eknilang that confirmed this: “Marshallese women suffer silently and…our culture and religion teaches us that reproductive abnormalities are a sign that women have been unfaithful to their husbands…for this reason many of my friends kept quiet about the strange births they had. In privacy, they gave birth not to children, but things they could only describe as octopuses, apples, turtles and other things in our experience. We do not have Marshallese words for these kinds of babies because they were never born before the radiation came.”[3]

In the end, I decided to include my own experiences in the piece to make the connections between the monsters we struggle with as mothers to the demons that the Marshallese women must have had to battle within themselves when they first experienced the trauma of birth defects. I asked myself, what if the mejenkwaad was not eating her child as a brutal act – but was instead attempting to return her child to her body – that in consuming her child, she was returning the child to her first home?

After finally finishing the piece, I filmed the poem after a day spent in Hiroshima Japan, in front of the Genbaku Dome (a very different dome) – the only building left standing near the hypocenter of the US bomb blast 72 years ago. It was an emotional and powerful day as I toured the Hiroshima Museum and met with a survivor – a hibakusha. She shared with me her own feelings of shame of being a hibakusha, and how she hid this from her own son. There were so many intersections with the nuclear legacy of the Marshalls . After our meeting we rushed to the Genbaku Dome to film. We had only 10 minutes because we had to run to catch a train, and it took only 2 takes (tourists and students kept walking into the shot).

Filming “Monster” in front of the Genbaku Dome in Hiroshima, one of the only buildings left standing after the US bomb blast 72 years ago

About a month later, I adapted the piece into a theatrical performance in a show called “She Who Dies to Live” that premiered at the Smithsonian pop up culture lab ‘Ae Kai in Hawai’i. That performance, alongside my friends, writers and artists Jocelyn Ng, Terisa Siagatonu, and Jahra Rager, was one of the most creatively satisfying experiences of my life.

Ultimately the poem represents for me where I want to focus more of my energy on: poems and creative work that are as much a journey as they are a product.

A still from our theater performance “She Who Dies to Live” a show which premiered at the Smithsonian Museum pop up culture lab ‘Ae Kai in Hawai’i.

Why hasn’t the RMI ratified the nuclear ban treaty?

ICAN later premiered the poem a few days before the treaty was adopted by the UN. I did a little celebration inside. Our country was one of the first to sign it.

But I was shocked a few months later to learn that we were noticeably absent in the list of countries that ratified. What had changed?

I have several theories but the one that seems most likely is that this decision is tied directly to our relationship to the US, and to provisions in our Compact that make it challenging for our country to confront the US on nuclear issues. Funding from the US constitutes a huge portion of our country’s annual budget – a budget which contributes to our education and health care systems. Funding could be cut. There is also a large amount of our people living in the US (myself included) for reasons ranging from family to healthcare (a lot of which is actually related the nuclear testing) to education and employment. Would our community be penalized if we voted against the US? In the age of Trump, anything is possible. A vote against the forces that once ravaged our islands and continues to cripple our country could result in real consequences against our already marginalized and struggling community. We already know what it’s like to have our voices ignored.

And these fears are not unfounded. My partner is from the US territory of American Samoa, but still has ties and family in the country of Samoa that has had their temporary visas banned. For what reason? Because of 3 deportations?

This is not paranoia or conspiracy theories. The age of Trump has given Americans and especially communities of color, women, and queer communities a newfound layer of fear and anxiety. Pacific Islanders are largely unheard or not considered in larger conversations in the media probably due to our relatively small population – though there’s plenty of us speaking out through various platforms. And there are even those who maintain their support of Trump. But blind allegiance and silence will not save us.

As I continue to edit and prepare the Runit Dome piece, I think of all these different layers, and pieces of the larger puzzle. In the similar pattern of “Monster” the “Dome Poem” is taking just as much time to research and to write. Unfortunately, I’ve had less than a month to write it (it took me about 3 months to write “Monster”). And so far, my biggest struggle is finding elders who are familiar with the legends and traditional stories of Enewetak and Runit who can meet with me here in Oregon where I’m currently based. But as with “Monster” I’m taking the time write and research this. I’m trying my best to focus more on the journey, rather than just the product.

Below is the page version of “Monster” while the video performance created for ICAN and filmed in Hiroshima can be viewed here.

Monster

Sometimes I wonder if Marshallese women are the chosen ones.

I wonder if someone selected us from a stack. Drew us out slow. Methodical. Then, issued the order:

Give birth to nightmares. Show the world what happens. When the sun explodes inside you.

How many stories of nuclear war are hidden in our bodies?

574 – the number of stillbirths and miscarriages after the bombs of 1951. Before the bombs? 52.

Bella Compoj told the UN she could no longer have children. That she saw her friends give birth to ugly things.

Nerik gave birth to something resembling the eggs of a sea turtle and Flora gave birth to something like the intestines [4]

She told this to a committee of men who washed their hands of this sin – these women who bore unholy things – created from exploding spit and ugly things.

And how these women buried their nightmares. Beneath a coconut tree. Pretended it never happened. Sinister. Hideous. Monster. More jellyfish than child.

And yet. They could see the chest inhale. Exhale. Could it be

human?

Nerik gave birth to something resembling the eggs of a sea turtle and Flora gave birth to something like intestines.

In our legends lives a monster. Mejenkwaad. Woman demons – unhinged jaws swallowing canoes, men, babies. Whole. Shark teeth in the backs of their head. Necks that stretch around an entire island, bloodthirsty. Hungry for babies and pregnant women. Monsters.

My three-year-old likes to hunt for monsters in our closet. We use the light of my cell phone. A blue glow in the dark. We whisper to each other – did you hear that?

Did I hear what?

The silence of my dreams is severed by her screaming nightmares. And I am a mewling mess turned monster huddled in the corner wide-eyed, wild haired, unable to touch, unable to care, unable to bear the exhaustion, anxiety clawing away at my chest. Am I even

human? Post-partum – easier to diagnose after the fact. Two years later those memories haunt me. When I became the bump in the night. When I realized I needed to protect her. From me.

Did you hear that?

Nerik gave birth to something resembling the eggs of a sea turtle and Flora gave birth to something like intestines.

In our legends lives a monster. Woman demons, unhinged jaws. Swallowing their own babies. Driven mad. Turned flesh rotten. Blood through their eyes their teeth their nose.

Were the women who gave birth to nightmares considered monsters? Were they driven mad by these unholy things that came from their bodies? Were they sick with the feeling of horror that perhaps there was something

wrong. With them.

My three-year-old sleeps next to me. I have lost my fangs and ugly dreams. I watch her chest inhale. Exhale. Know that she is real, she is mine. I try to write forgiveness and healing into our story. Into myself.

In legends lives a woman. Turned monster from loneliness. Turned monster from agony and suns exploding in her chest. She gives birth to a child that is not so much a child but too much a jellyfish. The child is struggling for breath. Struggling in pain. She wants to bring the child peace. Bring her home. Her first home. Inside her body.

It is an embrace. It is only. An embrace. She kneels next to the body.

And inhales.

[1] Defense Nuclear Agency, The Radiological Cleanup of Enewetak Atoll, DARE# 27293 (Washington, DC:

Defense Nuclear Agency, 1981), 330, 408, 418, 428-31, 441, 444.

[2] Jack Tobin, Stories from the Marshall Islands (Honolulu, HI, University of Hawaii Press: 2002) 188.

[3] Health Research Bulletin, “Marshall Islands Stand at New “Crossroads”… (Washington, DC: Physicians for Social Responsibility, 1996), 19.

[4] Glenn Alcalay, “The Sociocultural Impact of Nuclear Weapons Tests in the Marshall Islands,” (unpublished field report: 1981) 1-2.

postpartum depression, a scary thing that not all women talk about, maybe becuase they don’t understand what it is? something that our health care system does not point out during a mother to be’s prenatal visits or even after delivery? I too can say that i was also a victim of postpartum depression. From reading and learning about pregnancy and life after, i learned that postpartum was a part of it all in which case some women experiience it while others don’t. I always thought mejenkwar was in some ways postpartum depression, i compared my feelings to stories that i had heard about women who went through horrifiying experiences such as trying to harm their own infants and or children, and i honestly could relate. Even after almost a decade ago, thinking back makes me shiver, scared. The feeling of helplessness creeps back in. I strongly believe that this is something that women need to bring to the light and talk more and openly about. Reach out to our health care workers and each other, and learn how to cope with this type of depression because it can take you to the darkest of places that you never imagined you’d be in.