My latest poem video has finally been released. This was a simpler poem video than my last one (Islands Dropped from a Basket) created for the Honolulu Biennial this past February. “Butterfly Thief” was a poem that was curated by an energy company in London called Good Energy whose mission is to “is to transform the UK energy market by helping homes and businesses to be part of a sustainable solution to climate change.” Originally, Good Energy approached me to perform at a literary arts festival in the UK called the Hay Festival. I couldn’t make it at the time – it was last year in May during the Festival of Pacific Arts in Guam. So instead they came up with a pretty interesting idea: they asked if I’d be interested in writing a “crowd-sourced poem.” They shared a video with festival attendees where I basically asked the crowd to write down ideas for my next climate change poem. Folks either wrote their responses down on cards, or tweeted them. Good Energy then put together the responses and sent them to me – telling me to come up with a poem from the crowd’s responses.

Interestingly enough, I noticed quite a few responses indicated concerns with the loss of bees and butterflies. There really aren’t that many bees and butterflies back home in the Marshalls, so this caught my attention. I did some basic online research, and found out that actually populations of both bees and butterflies are facing extinction – one of the reasons contributing to this threat is climate change.

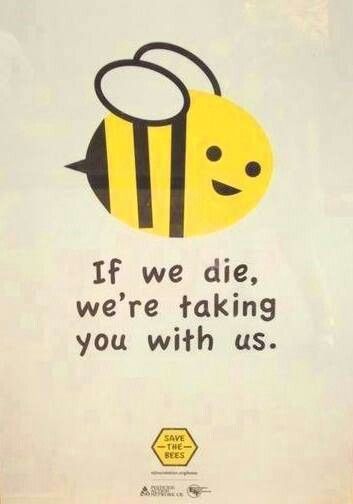

During my research I came across a cartoon, that helped me begin to shape the poem:

I decided to connect this impending loss with the impending loss of our islands.

A Note on Disappearing Islands and Complex Narratives

The year before, leading up to the Paris COP21 climate talks in November 2015, I heard from family members and friends about an apparent island along the Majuro atoll that had disappeared because of the rising tides. My friends and I took a boat ride to Kalalen* – the last island before the channel that enters the lagoon of Majuro to see what we could find (see the map below).

On Kalalen I spoke to a man named Yoster Harris, ri-alap, or the land owner/over-seer at Kalalen. As soon as I got off the boat, he came to me, gripping my hand with an urgency, telling me in Marshallese that he’d been waiting for me.

According to Yoster, a pile of sand and rocks that was only a few feet away called Ellekan was once a full island. He said 10 years ago, it was lush and full of coconut and pandanus trees – that he used to walk across the reef at low tide, and sleep and camp there overnight, sometimes even finding crabs to bring back to eat. He said 10 years later, because of the constant high tides washing over the island, it has become barren. This, according to Yoster, is all a result of climate change. He said in Marshallese, “We’ve had the funeral for that island – it’s over. But you need to save the others.” I came away from the experience feeling the weight of Yoster’s appeal, as well as the chilling realization that the pile of sand and rocks that was once an island is exactly what the rest of the Marshall Islands could look like in a few years.

Ellekan – the island referenced in my poem that, according to landowner Yoster Harris, was lush and full of coconut trees 10 years ago.

We have yet to bring scientists to Ellekan to confirm Yoster’s suspicions of climate change as the cause of it’s disappearance. This confirmation from outsiders is needed in this day and age of scientists and global conferences – but Yoster says he’s been living on Kalalen most of his life, and as a result is a witness first-hand to the effects of climate change. And yet anecdotal stories from indigenous islanders such as Yoster continue to be viewed with suspicion by outsiders, and even other islanders themselves – I heard conflicting stories of Ellekan from other Marshallese.

A recent story from the Guardian confirms this narrative – 5 islands from the Solomon Islands have just been confirmed to have disappeared as a result of climate change by scientists from Australia. And yet how long were Solomon islanders themselves aware of these islands? Had they been telling this story all along? Does this mean that the disappearance of islands does not warrant an international outcry unless science confirms the story? According to the article, the study is the first that “scientifically ‘confirms the numerous anecdotal accounts from across the Pacific of the dramatic impacts of climate change on coastlines and people.'”

Which brings to mind another question – how much of the responses/suspicions from other Marshallese to Yoster’s story is founded on actual evidence, and how much is motivated by the internalized colonialist mindset that needs the confirmation of outsiders and scientists to affirm indigenous knowledge?

The fact of the matter is, from my limited experience within the climate realm, it’s clear that anecdotal indigenous experiences are valued up to a point – when it comes to hard evidence, and weightier arguments for negotiations, climate science will be prioritized over indigenous knowledge.

I had reservations about including these complex issues around the story of this island in this blog post – but I do believe these are necessary conversations to be had. In the end, I decided to include this story in the final poem – because it is a powerful story, and because I chose to prioritize indigenous knowledge and Yoster’s generosity in sharing his experience and his perspectives with me.

So without further ado, here is the final piece.

Butterfly Thief

In middle school

I was a butterfly thief

I stole caterpillars, rolled into cocoons

from a bush outside our classrooms

I nestled them into leaves on top of my desk across

from my bunkbed and

a few weeks later I woke

to a morning light of trembling butterflies

I read recently

that 40% of pollinator species

including butterflies and bees

are facing extinction

One of the key causes?

Climate change

Unusually warm winters force plants

to shift their schedules. When a bee

comes out of hibernation

the flowers it needs to feed on has already

bloomed and died

Populations of the rusty patched bumble bee

and monarch butterfly

has already declined by 80%

I came across a cartoon

that showed a bumble bee

cute tubby and smiling

with a message in a little cartoon bubble

If we die

we’re taking you with us

Might as well put a Marshallese face

over that bumble bee

Because if our islands drown out

due to the rising sea level

just who do you think

will be next

I’m taking you with me

Another contributing factor

to the death of bees and butterflies

are pesticides. For bees, the pesticides cloud their vision.

They lose their way and die

before they reach their home

How many of us

will die before we get to go home

will take a boat to islands that were once whole

once held a hive of community

now reduced to sand and stone

Some stories say our ancestors came from volcano stone

Lidrepdrepju – a basalt rock goddess rooted in reef

Today I keep a basalt rock on my bookshelf

What tokens of our land shall we/will we

store in our selves

inside our honeycomb of chest bones

the buzzing of a shore long gone

I’m taking you with me

Today my newsfeed erupted

with the announcement

that CEO of Exxon Mobile Rex Tillerson

was named Secretary of State

by US President Donald Trump

Exxon Mobile knew of climate change in 1981

But funded climate deniers

for 27 years

So whose colony is it collapsing today?

Is it just the bees?

Or is it also the human race

funding the world to be washed into the sea?

Trust –

I’m taking you with me

On a visit to Kalalan Island

a man takes my hand and swears

he was waiting for me. He points

to another island named Ellekan

just a few waves away

He says only 10 years ago

that island was lush. Full of coconut and pandanus trees. Now

just a pile of sand and stone. He says what’s dead

is dead. You can’t save this one

but you gotta save the others

The Prime Minister of Tuvalu was quoted as saying

if we save Tuvalu

we save the world

But what if we don’t save Tuvalu

what if bees and butterflies become extinct

what if our/my islands don’t survive

just who

do you think

will be next?

I’m taking you with me

I’m taking you with me

I’m taking you with me