Iakwe aolep – it’s been a while since my last blog post. Last year was hectic and instead of updating my blog alongside my social media I fell off the map after my journey to Enewetak. So to kick off this year’s blog posts I’d like to focus on coming to terms with a new piece of advice given to our island government this past summer: artificial islands and/or elevation.

This was covered a few months ago by journalist Jon Letman for National Geographic. I would highly recommend reading the full article here. This idea of elevation or artificial islands was delivered to us by climate scientist Dr. Chip Fletcher in July at our second national climate conference in our state capitol, Majuro. I was amongst the audience members who “audibly gasped” when he showed projections of our airport under water after only a foot of sea level rise. His recommendation was that if we wanted to stay in our islands we needed to begin seriously considering elevating our islands or building artificial islands to move to.

Artificial islands are not a new concept. I’m not sure when I first came across them but I remember the feeling of disgust that while thousands of islanders were contemplating losing our homes, there were billionaires building islands in the shape of a heart as a luxury getaway.

And while our government is only now exploring this option as a real strategy, Kiribati’s former President Anote Tong was already discussing this back in 2016. At the time, their government met with UAE developers to learn more about the process, and met with with Japanese engineering firm Shimizu in 2018, who suggested a “futuristic floating-island” concept, that was estimated at $450 billion.

Like Kiribati, it seems ridiculous that Marshall Islands only contributes 0.00001% of global emissions and yet we are now being forced to consider possibilities we would never have considered before, with money we don’t have. Of course, it’s impractical to even suggest that we foot the bill for this – it would obviously need to be funded by those countries, or those corporations, contributing the most emissions.

Artificial Islands: An Opportunity?

Either way, this may be old news for some, but it’s a turning point for us. One that deserves to be marked. Up till now, we’ve essentially shouted the fact that we refuse to leave our islands (or maybe I shouted). I’ve told audiences over and over that “there’s still time” and to have hope. But with the recent release of IPCC report on 1.5, and the current political climate, even I’ve begun to reevaluate the meaning of hope, or at least “interrogate the discourse of hope” as my friend Julian once mentioned in a conversation. I know that building artificial islands doesn’t mean we’ve given up all hope. But we’re definitely losing something.

I should note that there are those of us who view this as an opportunity – an opportunity to pioneer new green technology and restore sustainable cultures through the revitalization of traditional values (assuming the funding comes through). I understand this perspective, and it has truth in it. But I’m not ready to embrace it. I can’t see this as an opportunity if we have no choice in the matter. Building islands or even just elevating would mean ripping apart our land, and with it the roots of our culture, as well as displacing/uprooting thousands of people in the process, and using processes that could destroy precious reefs. It’s extreme, and desperate.

I had a follow-up conversation with Dr. Fletcher about a month later. We both agreed that our country needs more support, and that his perspective wasn’t the only one we needed to consider. We discussed the grief that comes with our work and how advocacy can take its toll. But we also agreed that practicality is necessary.

“Change is inevitable and we have brought upon ourselves an era of rapid global damaging change,” he explained over the phone. “We can react out of denial or we can react out of recognition and the two climate change pathways – one being mitigation, the other being adaptation – those provide a channeling for our emotions. We can continue to hope, and that’s what mitigation is about. And we have to get realistic and not put all our eggs in the basket labeled hope and realize what’s happening and that’s what adaptation is about. We have to follow both pathways – adaptation to protect ourselves and mitigation to protect our children.”

I’m not a scientist, marine biologist, or architect – my ability to wrap my mind around this issue is limited. I haven’t even known where to begin. Luckily there are local Marshallese experts with a history of studying our reefs and our island topography who might be able to speak to paths forward better, most notably the Coastal Management Advisory Council (CMAC). As we move forward with strategies, I would hope we would rely on our own people, just as much as outside innovators.

That being said, my work has never been about drawing ground breaking scientific conclusions, or coordinating international strategies – it’s always been about processing the emotional weight of climate change through art. So that’s what I’ve been doing for the past few months.

Artificial Islands: Rituals for Grief

A lot of my artistic work last year centered around the idea of rituals, and creating rituals to process grief. In “Anointed” I drew on our Marshallese funeral ritual, the eorak – the last stage of our funeral rites when we scatter white stones from woven baskets around the grave site to represent a cleansing. I transposed this to the Runit dome, where I used a woven basket and white stones to represent a ritual of grieving and cleansing for the island of Runit, before it became a “tomb.” I decided to do this after realizing that the poem I wrote, written to Runit, was essentially a mourning poem – mourning the land that Runit was before it became a nuclear waste site.

I once again pulled on ritual in our poem video “Rise” for the 350.org campaign in August. I worked with my poet collaborator (my “sister of ice and snow”) Greenlandic native poet Aka Niviâna, to create a ritual of exchange. The video was about my journey to meet her in Greenland, where we would exchange gifts from our lands that held stories of our culture, resilience, and legends at the top of an ice sheet. This exchange of gifts is another common ritual, one I’ve witnessed many times – whether it’s presenting school supplies and bags of rice in Enewetak or watching the delegates from Samoa, Pohnpei, and the RMI exchange gifts of woven mats and cases of canned tuna before an educational conference in Palau.

For our video, we exchanged stones and shells. Aka gave me stones from the shores of Nuuk, her home town, while I gave her shells I picked from the shores of the Runit Dome and Bikini Atoll during our “Anointed” video shooting. We filmed the poem less than a month after the climate conference Dr. Fletcher presented at, and I inserted this new information into the poem:

“Let me show you

airports underwater

bulldozed reefs

blasted sands

and plans to build new atolls

forcing land from an ancient rising sea”

In October I focused on this topic again to appeal to a group of architects, engineers, designers, and artists in Tokyo at the Innovative City Forum, where I delivered a keynote “Island Cities Under Water: The Case for the Marshall Islands,” outlining the history of the Marshalls, our relationship to Japan, and our new issue of artificial islands. I attempted to advocate for art, for making room to grieve.

It was a valuable opportunity, as this was a group of innovators who were also invested in the idea of green and sustainable technology, and who made casual statements like “building artificial islands are easy.” I was able to make some connections and get some ideas, but ultimately came home feeling drained, and still at a loss for answers.

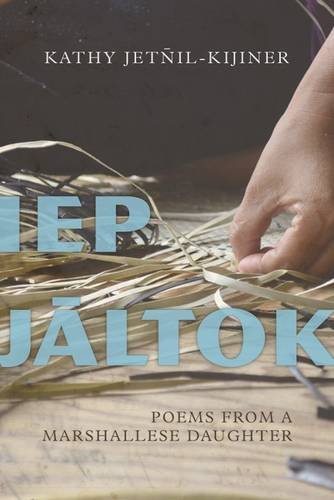

I processed it one last time in November, this time in front of gallery audiences in a performance for the 9th Asia Pacific Triennial in Australia at the Queensland Art Gallery. “Lorro: Of Wings and Seas” was a performance I wrote that incorporated stories from the weaving workshops I took in 2017 with Marshallese master weaver Terse Timothy and stories of Marshallese women demons the mejenkwaad and the lorro. It was also my first time to dig deeper into the the connection between violence against women and land.

“Look –

I missed a strand.

I missed a strand, and now could we be unraveling?

Has the day come when we can talk? Maybe the day has come when we must talk. Because something is eating islands. There are islands dying. There are voices telling us to destroy thousand year old limbs like it’s nothing.

Like it’s not another strand unraveling. Like it’s not another woman sinking to the bottom. Sinking boulders tied to feet, body caged in a woven tomb.

We missed a strand and we named her monster. We tell stories about her teeth. We tell stories about how we saw a slit from her head down her back open, shark teeth lying in wait, edges sharp for consuming, but we forgot/we forget/we missed a strand/ we are all made of teeth.”

For that performance, I used a ritual of painting my hands and face with white paint to transition from stories of my weaving worksop to embodying the character of the mejenkwaad/lorro. This is not rooted in anything traditional or Marshallese – but I needed a simple way of marking that transition that would allow me to transcend the physical, tangible world of the weaving hut into the spiritual, metaphysical world of our ancestors.

Photograph: Natasha Harth / Image courtesy: QAGOMA

Photograph: Natasha Harth / Image courtesy: QAGOMA

Photograph: Natasha Harth / Image courtesy: QAGOMA

Ultimately I’ve found these rituals cleansing for digesting the raw grief that comes with this news. But I can also feel myself craving real solutions, tangible ones I can hold in my hands. And that, unfortunately won’t be coming right away. Until then, more processing is necessary, as well as a clear, collective vision of a way forward that makes no concessions. We’ve already made enough – forced – comprises as it is.