Vanuatu Warrior Isso serves kava to a representative from German activist group Ende Gelände and local citizens initiative Buirer für Buir. Photos from 350

It’s been over two weeks since I left COP23, and I’m only now beginning to unravel what I learned. When I started this blog post, it was meant to be a broad overview of this recent conference – but I ended up focused on one of our actions that began our trip: a traditional Fijian ceremony we held alongside the shutdown of a coal mine.

My trip was sponsored by the German non-profit Bread for the World. But the events they required me at was limited, so most of my free time was spent alongside other youth Pacific islander activists and organizers, all from the 350.org team known as the Pacific Climate Warriors. In total, there were 12 of us in Bonn, representing at least 9 island nations.

Fijian Warrior and Pacific Regional Coordinator Fenton Lutunatabua served as a bridge between us islanders and the european team, and helped organize actions not just within the COP but also outside of it. Which brings me to the main topic for this blogpost: our action alongside German activists on November 5. An experience I won’t be forgetting soon.

Manheim – an abandoned reminder

The coal mine that was the focus of this action is near Hambuch, and is said to be “the biggest hole in Europe” and “one of the largest contributors of carbon on the continent,” according to the Guardian. Coal power supplied about 40 percent of all Germany’s electricity last year, but about a third of its carbon dioxide pollution. Chancellor Merkel’s position on coal was something we eagerly awaited throughout the conference.

It was alongside this coal mine in a sleepy town near Manheim that our team organized and held a traditional Fijian sevusevu ceremony at sunrise. The sevusevu, which was primarily led and facilitated by George Nacewa, a Fijian warrior, is a ceremony in which leaders from one village meet with another to ask for permission to enter their land. In this case, the ceremony was held between the warriors and German organizers from the activist group Ende Gelände.

The ceremony was meant to be a demonstration of solidarity with a massive action led by Ende Gelände activists just a few hours later. Thousands of protesters would be descending on the coal mine just a few miles away to use their bodies to block the machines and demand an end to fossil fuels.

The morning we went to Manheim, was a cold, frigid day – and rainy. The bus ride over was a dark, hour-long ride, filled with napping, cracking jokes, blasting songs, and sharing cheese sandwiches. At one point a member pointed out what looked like the rising sun – only to realize it was a massive flame shooting from a coal stack.

When we finally arrived, we exited the bus to an abandoned town filled with brick houses and empty streets. Heavy fog curled around our bus. I was told the village was relocated due to the expansion of the mine. Today, it’s used to house refugees. The irony and the double-standard was not lost on us. We shivered as we made our way into the church with our tapa cloths.

Tapa flower petals – an offering

The tapa cloths were brought to Germany by our Tongan Warriors, Siliveseteli Loloa and Joseph-Zane Sikulu, and were our offering to the Ende Gelände during the sevusevu.

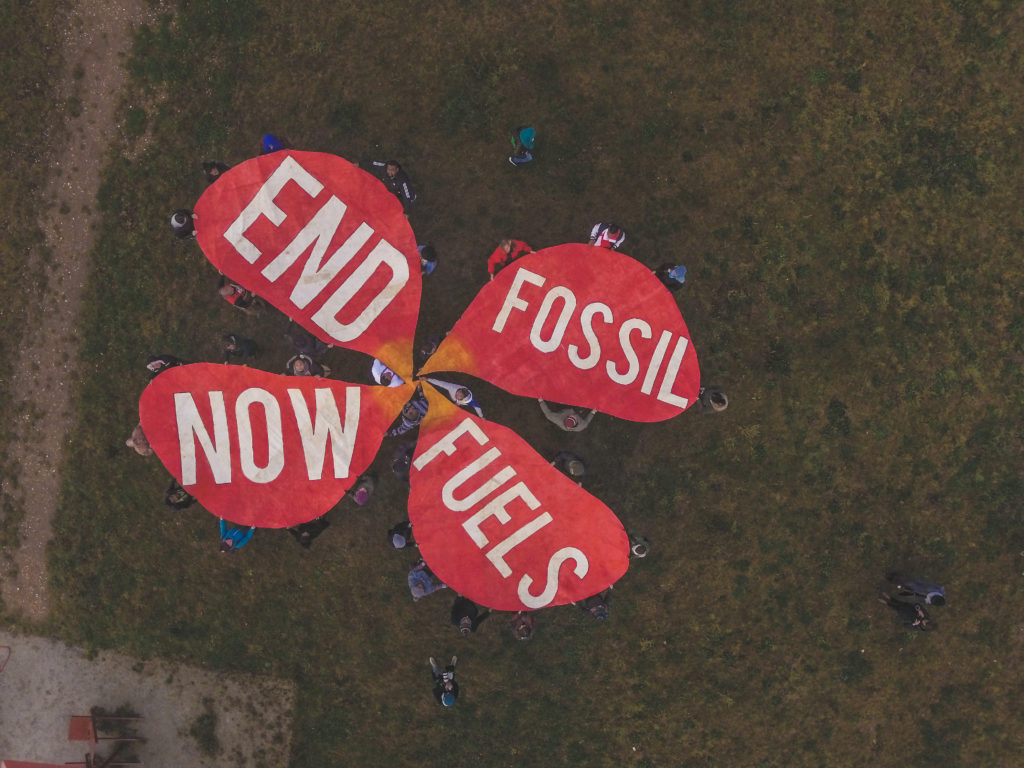

The tapa brought to Germany was cut into 4 massive flower-shaped petals, handmade and painted with the words “End Fossil Fuel Now.” The flower shape was chosen to fit in line with our #HaveYourSei campaign, which used the symbol of the islander flower to represent the beauty and resilience of our cultures and people.

I don’t think I’ll forget that morning. In a circle, we held hands and said a prayer of intention, donned our traditional wear, lined up, then took off our coats. The men of our group took off their socks and shoes. Outside, a conch shell blew. Jokes were whispered but once the cold air hit us, and we could see the crowd waiting, we were enveloped in silence. The ceremony began.

A Sevusevu in German Rain

After the ceremony, some of our RMI government team teased me good-naturedly about being barefoot in the rain. I told them it was intentional. We were asked to remove our coats and shoes as a sign of humility. Zane later told me the story of the Tongan princess who walked for miles barefoot in the rain with no umbrella to visit the British Queen. It demonstrated her respect, humility, and strength.

I mostly thought about controlling my shivering. We walked out to where the ceremony was held in the middle of the street. The Ende Gelände representatives were seated on chairs at one end. Our men sat on the other end facing them, proud backs tall, unflinching against the cold. Surrounding us was a lagoon of German onlookers, community members, media representatives, all covered in thick black coats, sheltered by umbrellas. Cameras and camera phones flashed.

The ceremony was quiet, calm. It began with a welcoming speech from Zane, a beautiful prayer from the Reverend James Bhagwan, from the Methodist Church in Fiji, followed by a powerful chant from George. Their voices reverberated in the silence and emptiness of the town. Kava was stirred, poured into rounded coconut husked cups, and served to the representatives. We clapped. We sighed. Our role as the women was to stand and bring the tapa cloths when it was time. Throughout the ceremony, it continued to rain. Puffs of cold air came from our breaths. The power of the ceremony, the first of its kind I’d ever witnessed, warmed me.

After the ceremony was over, some of us were asked to give interviews. “The action conducted by Ende Gelände later is illegal,” the interviewer said, the lens of a video camera unblinking. “What are your thoughts on actions such as those – do you support them?”

Legal and illegal actions – can they co-exist?

I thought about this question and discussed it more than once with our team. When I first joined the Warriors earlier this year (I’m a bit of a newbie), I noted how the leaders emphasized that actions warriors participated in would be nonviolent, and legal. As someone raised in Hawai’i, under a heavy influence of the US, I’ve seen a lot of actions that begin that way – but then turn ugly. Sometimes it’s the protestors. A lot of times it isn’t. So I initially found this curious, but understood the reasoning later.

This decision recognizes many of our islanders are uncomfortable with western actions like the ones staged by Ende Gelände. They challenge authority and do so in ways that go against the grain of our cultural teachings of humility and respect. It’s a struggle for us as an already marginalized population – many of our group members can’t risk violence or jail sentences, due to poor job security or responsibilities to extended families. In fact, some feel uncomfortable being labeled an “activist” at all – a term that brings to mind foreigners doing outrageous things for outrageous causes. “To be a Pacific Climate Warrior means to be strictly non-violent and to stand strongly in a dignified and peaceful manner for the future of the Pacific Islands,” states a 350 Pacific page, “A warrior is resilient. A warrior is not aggressive or violent, but is assertive. A warrior serves to protect their community, culture, land and ocean. A warrior is always learning.”

Fenton and our previous team leader Koreti understood that protest can take many shapes and forms. It can even take the shape of cultural humility. In this case, the sevusevu was an act of humility but also one that put a Pacific culture in the forefront. It highlighted Pacific values, and created a connection through an ancient tradition between a town displaced by the same insidious forces swallowing our islands. I was reminded of the stories I’d heard of our chiefs and landowners who once sailed to the US occupied Kwajalein atoll in protest.

Later, one of the representatives who drank the kava, told us, in tears, that she was overwhelmed by the respect and beauty of our gesture. Antje Grothus is from the village Buir in the Rhineland. She is with the local citizens’ initiative Buirer für Buir that is working to keep coal in the ground. She and her family and community are directly affected by coal extraction. “The ceremony was very moving,” she said, “but I also found it very shameful that the Pacific Climate Warriors asked us for permission to be here, and all the while we destroy their habitat by burning coal.”

The ceremony solidified the connections between our countries and our common struggle – how one decision can affect the survival of a people thousands of miles away. How an evacuated town can look and feel like an island gasping for air.

We found out later that while most of the action was peaceful, that some protesters were pepper sprayed by the police officers and some were jailed. In some ways, I felt as if what we did was not enough. Should we be out there too? Should we be putting our bodies on the line as well?

photo credit:https://www.ksta.de/region/rhein-erft/kerpen/-ende-gelaende–hunderte-aktivsten-dringen-in-tagebau-ein-28768600

I had to remind myself that our bodies are already on the line. Our oceans, our land, the survival of our cultures and identity. What we did, in a lot of ways, was powerful.

At this point in my journey, I’m learning that there is no one way to protest.

I met an activist from Ende Gelände later during another event, an Interfaith Panel. During her introduction, she explained that the faith of Ende Gelände is placed in illegal actions. I later asked her why this was such an important part of their beliefs. “When injustice becomes the law,” she said, “then breaking the law becomes just. We believe we are breaking the law for the right reasons.” I’d never heard this perspective – I found it refreshing and breathtaking.

I’ll continue to tiptoe around the concept of illegal actions, and processing what our/my contributions could look like. But I do believe that there is space for different forms of protest to exist. When done right, through communication and mutual respect, it can even complement one another. The partnership with Ende Gelände would not have gone so well, if it wasn’t for the hours of skype calls, and preparation that was facilitated by the 350 European team, and our coordinators Fenton and Zane. Though it lasted under an hour, many hands went into making sure that hour was impactful.

At the edge of a coal mine

Worn out and a bit damp after the ceremony, we filed into our bus. Before heading back to Bonn, we decided to head to the edge of the coal mine itself – there was an overlook there where we could see it before it became flooded with protesters.

I don’t know what I expected. To be honest, I think I was imagining one of those cartoon mines that was in a mountain, with the little metal bins like a roller coaster ride coming out of it. What I didn’t picture was a gash in the earth – a moonscape of emptiness, scraped clean and raw.

Against the edge of the overlook were plastic lawn chairs for people to sunbathe or relax while presumably “enjoying” the view. In front was a clunky metal playground.

As we walked to the edge, I only thought about lines of poetry to try and capture what I was seeing – how this emptiness felt so familiar. As if I’d seen it before. I wondered if this is what Runit looked like before it was filled with nuclear waste and covered in a concrete dome.

Many of us cried. That this was what our islands were going under for – the ugliness of it was nothing we’d expected. It brought us home to why we were all in this fight.

A video was taken of our reaction to seeing the mine. Afterwards Tia, our Tokelauan warrior, led us in our customary chant: “We are not drowning – we are fighting!”

The first round of the chant felt hollow. This was when I felt tears in my eyes – I felt so helpless and useless. But as we kept saying it, I forced myself to draw strength from the others around me. I felt myself being lifted as if someone was saying yes. Yes. This is why you’re here.

Afterwards, we unrolled the tapa petals, and stood together holding the edges, craning our necks upward, searching for the drone. The sky was clearer than ever. Brilliant blue with a sun blinding our eyes.

Poem from George

The following day, we had a debrief with the 350 team. There was a writing workshop, reflecting on the day before, and afterwards we all shared a poem. All of the poems were beautiful. I asked George to share his not just because it moved me, but also as an homage to the work and the leadership he provided to make the ceremony possible, one that was beautiful, and an honor to witness:

Yesterday

sounded like the calm ocean breeze blowing through the Baka Tree. The laughter of my Dreu’s making jokes about the Baigani incident. The mixing of Yaqona at 10am and the call from across the village going mai, mai, mai, dua mada na bilinimua.

Yesterday tasted like sui mada by my mother. Fresh fish and Yaqona made by my people.

Yesterday looked like the Bula smiles and respectful gaze of my elders. It looked like hope.

Yesterday smelt like the voivoi picked to weave the finest mats, like the masi used to wrap my son and daughter the first time they came home.

Yesterday felt like

We are not drowning.

We are fighting.

**translations:

Yaqona – Kava

Mai, mai, mai, dua mada na bili ni mua – come, come, come, one farewell mix

Sui – meaty bone soup

Voivoi – pandanus leaves

Masi – Tapa

Baigani – Egg plant

Drue’s – traditional address for people from Vanua Levu, the other bigger island in Fiji.

Thank you so much for sharing this with us.

We will never give up

” We are not drowning, we are fighting”.

Thank you for your words and pictures. It is so good to know that there are people dreaming dreams like ours all over the world. It is so good to know that you exist. It is so good to hear your words, learn of your ways of doing things, be reminded of gentleness and humility in the midst of the struggle with the greed that tears up our earth with no care for her or for any who might live on her. I live in England, I will remember you and your people now. If we hold onto one another around the world, then we can strengthen one another – so do not forget us – we do not forget you, annie

Kathy, this is absolutely gorgeous. Thanks for sharing your reflections with us.