“Im eor jet rej buromoj im rej ettor im armej rej jibwe er mokta jan aer ekkake.”

“And, there were some who were buromoj [afflicted by melancholia or grief], and they run, and people seize them, before they can fly away.”

(266, 262) “Story about lōrro” ribwebenato Jelibor Jam, 1975. Stories from the Marshall Islands. Jack Tobin.

Grounded

Anchor yourself outside her room. A jaki

to sleep on, a cooler for drinks. Hands flexed

and prepared to ground her in this life.

There are some who grieve –

the weight there heavier than lead but you

grab hold of their ankles before

they can depart. You offer remedies –

a gloved hand against their face.

A mask-spoken word. Sadness pulls

us all beneath the waves. Endrein

you say when your mother enters

the hospital. Life is like this. You accept.

So many years pulling others from flight

harsh hospital ward alight

but who grounds you?

If I follow the family line to the sand below

which ancestors will still be anchored there

beside someone healing, someone asleep?

Offering remedies for grief. Instructions

for which leaf to boil, soft hands to soothe

the right chant to whisper into their ear

Would you have needed

to demand your safety then too?

Would we have listened to you?

Behind the poem

With everything I’ve been balancing as both Climate Envoy for our government, and as Director of our nonprofit Jo-Jikum, it’s harder to write these days. But an artist friend of mine here in Majuro approached me looking to collaborate on a project together – I’d write the poem, and he’d paint a mural inspired by the piece. It felt good to do something creative that wasn’t meant for a campaign, or pushed by a deadline. We decided nurses and doctors, those on the front lines, could use all the support. So I wrote this poem above, pulling together multiple threads of ideas and concepts. It’s inspired by my fear for nurses and doctors, my cousin who’s a nurse, the healers and caretakers who have always been a part of our culture, and – somehow, wildly – the lōrro.

The different threads

My cousin has been a caretaker for much of her life, and is also a nurse who regularly works in both the hospital and the outerislands. The poem is about my fear for her, and so many in her field of work, especially after seeing the rise of deaths and even suicides of nurses and doctors around the world, being sent to the front lines without any protective gear, without the institutional support they so need.

My aunt, my cousin’s mother, recently entered the hospital. I admired the way my cousin shifted from nurse to caretaker immediately. It’s not just a job or occupation for her. It’s who she is. There’s a very specific way in which Marshallese family members support and nurse – “ri-kau” will sleep around the clock at the hospital. They’ll take shifts, bring with them coolers of drinks and food so that they never leave the side of the patients, they’ll massage their family members. They’ll bring mats, or jaki, and pillows and blankets to sleep next to patients’ beds on the hospital floors.

Confession: I’ve never been a great ri-kau. This is why I have nothing but admiration for caretakers and nurses. I have yet to fully embrace or understand that role, but for most Marshallese women, it’s second nature. I’m uncomfortable, and frankly afraid, of hospitals. So for now, until I can begin to practice this role, I offer a poem. A small token.

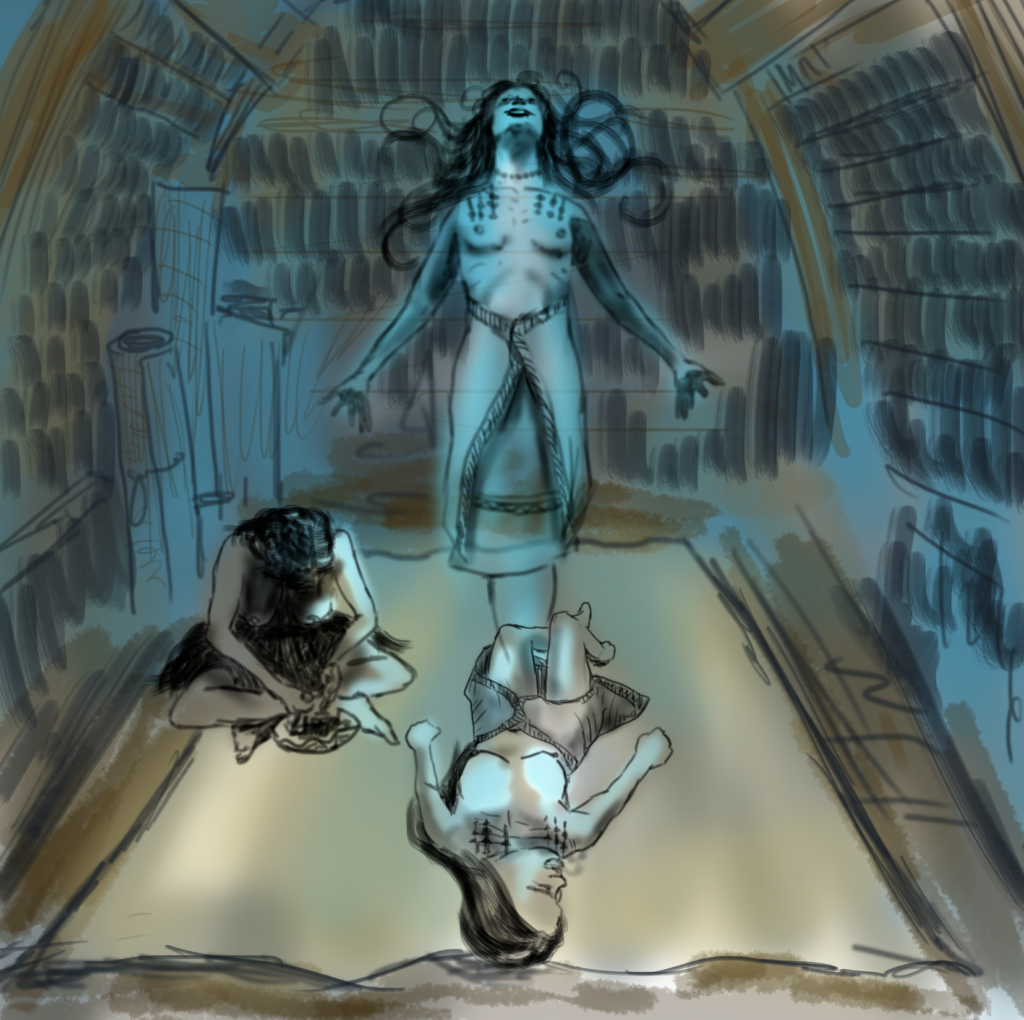

Another source of inspiration was the lōrro. I thought I was done writing about the lōrro, the Marshallese legend character of the woman who flies from island to island from grief over a lost love and broken heart. But the line that inspired the poem I wrote came from a legend about the lōrro.

For rimajel reading this post, I’ve done a lot of writing about both the lōrro and the mejenkwaad. Most of that writing has been to re-imagine these characters, humanize and understand them as more than a villain or a ghost. For this poem, I re-imagined the grief that makes the lōrro fly. Instead of grief over a lost love or a cheating spouse, I re-imagined the grief that must come for every person clinging between life and death, grief over leaving their loved ones behind, a grief so powerful it makes them fly.